Curating the Sublime Experience via Light in the Photographic.

A month long fellowship research project written up in this paper that researched how artworks, installations, religious spaces and the city of Venice itself provide the potential for a sublime experience through the curation of light, shadow and unknown.

Lumen is a body of research that investigated how light can connect a viewer to the sublime through photography. I created ephemeral photographic installations along the river Humber that captured light from sunrise to sunset, in differing seasons and terrains. Since then, individual images have been shown across the world including at Arles 2019 with The British Journal of Photography. Lumen will have its first solo show in autumn 2020 at the Ropewalk Gallery next to the river where it was made; a fitting inaugural full exhibition for this body of work and the opportunity to fully realise its intentions. My aim is to create the opportunity in this exhibition for the viewer to connect with the sublime.

How can the work be curated to facilitate this experience and resolve the concept of this project?

Fig.1 Lumen, Verity Adriana, 2015.

Edmund Burke described the sublime as a feeling that arises from being overwhelmed by external forces such as the grandeur of nature, whereas Immanuel Kant believed it to be a subjective conception that happens in the mind – a reaction to the perception of something beyond our capacity for control, and Joseph Hegel suggested it is a personal connection to God. The sublime experience is a gap in our understanding, a connection to something outside of ourselves.

As the most powerful creator of light in our solar system the sun is so bright that we cannot directly look at it, and so we cannot ever fully comprehend this primordial celestial force. The sun is sublime and our connection to it is the light that it beams to us through the universe. Photography’s reliance on light and dark within the camera itself, processing methodologies and viewing photographs means it is the ideal vehicle to explore our connection to the sublime. Jean-Francois Lyotard said that the sublime feeling is a crisis of communication brought on by that which exists outside of human parameters of description. He was interested in the idea of ‘the uncommunicable’ when translated by the creative process, and so the representation of the sublime in art becomes about presenting the unpresentable in presentation itself.

So how then can I present Lumen, a body of work about connecting to the sublime through the light of photography, if this is attempting the impossible?

Burke argues that there are key factors in the sublime such as vastness, light, darkness and so on. I used my time in Venice to research how the artists, architecture and the city itself provides sublimity with the aim of exploring how to achieve this in the presentation of Lumen.

Exploring the light of the Biennale

The work I spent the most time with as a steward at the British Pavilion was the artist Cathy Wilkes’ exhibition. Spending eight hours a day with work that is so minimal, and delicate makes the observer really look. I noticed every detail about the pieces and discussed how it was being interpreted with others, including fellow stewards and gallery visitors. A reaction I heard most often was that the space in the first room was so bright it became almost bleak. Many visitors said they found it almost difficult to see, as the space was so big and ceiling so high and light so bright with white walls and minimal art works. I realised that through this manipulation of sense perception the room felt, in photographic terms, overexposed which created a feeling of being disoriented.

The light in the space was as considered as the artwork and was completely natural at the decision of Wilkes and curator Dr Zoe Whitely, meaning that each gallery room changed as the light outside changed. On days when it rained the space became darker and almost dull and the whole show changed in tone, as did visitor reactions. On the days the sunshine was very bright outside with the hot Italian sun, it became bright and, in some rooms, overpowering. At certain times of day, beautiful dazzling light patterns would emerge and dance around the space, often interacting with the work itself, creating illuminations on certain objects and an almost ritualistic atmosphere. I wondered how different the exhibition would look and be received in the changing seasons.

Fig 2. Light observed in the British Pavilion Cathy Wilkes exhibition, August 2019.

To provide my research with varying perspectives I visited different pavilions and collateral events and discovered that An Odyssey by Vesko Gagović of the Montenegro pavilion gave insight into how curation can play a key part in the viewer experience of artworks. Large monolithic blocks of various sizes dominate the separate rooms they inhabit forcing the viewer to walk around them and observe them from different angles. The rooms are lit by the neon lighting coming from underneath each block, suggesting something spectacular emanating from within, making me think of the big bang and the origins of the universe. The atmosphere created by this lighting and the darkness within the space is one of tension and power. Each room becomes a curiosity to traverse, an unknown as to what will be in the next. This feeling of mystery triggered a physical reaction within me I sensed by the atmosphere of light and dark and the gold block that represented the sun, the source of almost all our natural light in our solar system. I understood a kind of religious undertone like worshipping at a monolithic altar. To exit I had to come back through the space, making me observe the works again which was when I saw a large strip of black tape peeling off the ceiling and hanging in the air, somewhat piercing the illusion of otherworldliness.

Fig 3. An Odyssey by Vesko Gagović at Venice Biennale 2019.

Gold seemed popular at the biennale this year, perhaps for its luminist qualities, it’s connection to the cosmos as an alien material, as in Odyssey, and to religious spaces, as seen in Lore Bert’s Illumination: Ways to Eureka at Chiesa San Samuele.

Bert focusses on Kant’s ideas around subjective perception with a large-scale installation of two tall square towers made from dichroic glass, a material that changes colour under different lighting conditions, emerging from a bed of individually twisted sheets of white tissue paper. By playing with the idea of colour perception and theory Bert intends the viewer to reflect on their experience of perception and senses within the space.

Fig 4. Lore Bert, Illumination: Ways to Eureka at Chiesa San Samuele.

The installation felt impinged by the lack of space and this impacted the opportunity to observe the light interacting with the glass, so I felt that the sensory intention of the work was much hindered. I reflected on the need for the work to fit with the space to facilitate a response, no matter how subjective. Whilst it could be said that this in fact supports Kant’s argument about personal perception, it felt as though Bert was attempting to guide us towards an idea that could not emanate within the given space via the materials and curation employed.

Ivan Lam’s work, One Inch, is a dark room lit only by a line of monitors facing the wall, mounted just one inch from its surface resulting in a digital glow and snippets of continuous sounds from the broadcasts on these screens. The viewer is plunged into darkness and must navigate around the space via the curious light from the monitors. The feeling of unknown as you enter the room through a dark curtain provided an experience from the beginning with which to interpret the works. This censorship of vision heightens the other senses and creates an eerie and almost ominous environment.

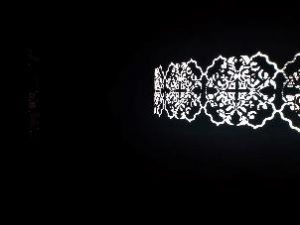

Orkhan Mammadov’s digital screen at the Azerbaijan pavilion is on a slowly turning wheel in the darkness, illuminated only by the light from its own display that shows evolving patterns emerging onto the screen, accompanied by a computational sound. These patterns are created by an algorithm processing fifteen thousand images of cultural items such as pots and ceramics with traditional national decorations. The installation of this work is successful because it deliberately plays with light and darkness to disarm the viewer, which is fitting for the content as algorithms and Artificial Intelligence could be described as a subject area unknown to many. Forcing the audience to enter this dark unfamiliar space and interact with a seemingly autonomous machine illuminated with the digital light that is at once familiar and foreboding made me think of works of religious art and religious spaces.

Fig 5. Orkhan Mammadov, Circular Repetition, 2019

Notes for Lumen exhibition:

- The use of light and dark creates an atmosphere of tension and ‘unknown’ and plays with sense perception. Dark spaces allow the viewer to observe light more and therefore connect with its power.

- Work with the gold colours prominent throughout Lumen to add to aura.

- Entering the space through a dark chamber seemed to add to the mystery and atmosphere of the works.

- Using digital/artificial light can work to create the right atmosphere, particularly when relevant to the works.

- Presentation of all works and supporting materials must be clean and perfect to reiterate the message of something otherworldly.

- The sizing and materials of the work must be coherent to the space, so the idea of the work is delivered.

Divine light in religious spaces in Venice.

Santa Maria Mirocoli, known as the marble church and distinctive for its materials and Florentine style, was built between 1481 and 1489. This church has survived relatively unchanged to this day and can still be seen as the architect intended; a vision of pale marble from floor to ceiling softly lit by the diffused light in the space. This, along with the gold ceiling, allows the light shining in from the clear glass windows to bounce around this beautiful building and create a bright aura that uplifts the spirit but does not overwhelm the senses.

Fig 6. Santa Maria dei Miracoli, Venice, 2019.

The light within Chiesa dei Carmini, a large church that dates to 1286, is made more prominent because of the dark columns, large dark paintings and heavy ritualistic censers. This creates a chiaroscuro effect by allowing the light to cut through the darker environment and highlight features providing a powerful reminder to the worshipper that divinity is apparent. I felt an atmosphere like that experienced in the installations of Gagovich and Lam.

Fig 7. Chiesa dei Carmini, Venice, 2019.

Scuola Grande di San Rocco was not a church but a ‘school’ or place for the confraternity of St Roch to carry out its work within the community. The spectacular large upper hall is adorned floor to ceiling with artworks, from the patterned marble floor to the carved dark wood sculptures and benches, to the gold ceiling adorned with paintings by Tintoretto. Where the bright sunlight from outside entered through the heavily draped windows it was dazzling and illuminated accents of the sculptures but obfuscated large areas of the dark paintings by bleaching them out to the eye as well as to my camera. The mathematical pattern of light and dark shapes on the marble floor was made glossy by this light, and the gold ceiling gleamed light, highlighting to me that each aspect of this grand hall had a part to play in the dance between light and dark in a process of revealing and concealing that plays with the connection to divinity.

Fig 8 Scuola San Rocco, Venice, 2019

Tintoretto’s luminist paintings decorate much of the hall and it’s ceiling and cleverly evoke the power of light through God in depictions from the bible. Light is represented as the literal divine intervention, a powerful force, an illuminating guide and a direct connection to deity. The luministic quality of these paintings feels as though Tintoretto understood connections to divinity through light in art, and that this helped play a part in the relationship of light and shadow in the building itself helping to create an divine experience for the Scuola’s members and visitors.

Fig 9a. The Eternal Father Appears to Moses, Tintoretto.

Fig 9b. The Baptism of Christ, Tintoretto.

The San Marco basilica is a mysterious looking building that was originally built in 828 and reportedly housed the body of St Mark that had been stolen from Alexandria. It was re-built in 1071 in Byzantine style with plundered gold, marble and treasure from the crusades in Constantinople. The basilica is a true spectacle inside, opulently decorated with gold, dark marble and mosaic depictions of the bible. This dark mysterious atmosphere seems befitting given the shady inception of this building, designed to house stolen bodies and loot and to showcase Venice as a world power. On my visit I overheard a tour guide explaining how worshippers used to be made to walk from East to West of the building following the path of the sun, in a ritual designed to cleanse the self of sin. Whether true or not, folklore like this means it is recognisable that the design of the basilica is interwoven with light to connect the worshipper to god. I imagined that if I had been able to visit without the hundreds of other people there, I would have felt completely overwhelmed by this space, (which reminded me of Wilkes’ requirements of fifteen visitors in the Pavilion gallery space at once to create a contemplative environment). The mystery and power of this building is established by the darkness that enables beams of light to shoot through the building as the sun moves around the circular cupolas, and the sheer spectacle of the gold, marble and art.

Fig 10. Light beam inside San Marco basilica, Venice, 2019.

Notes for Lumen exhibition:

- Ropewalk is a white gallery space and could be brightly lit but this would not create the right atmosphere.

- Creating a darker environment through controlled lighting and positioning of artworks will provide more of the ingredients for the sublime experience as noted in my research.

- A contemplative atmosphere will be needed. Although I won’t have to worry about large crowds as in Venice, a warning notice about lighting and intended noise levels could be arranged for before entering the space.

- Materials and objects that reflect light and create an aura in the space could be displayed such, as the actual screens from the Lumen images.

The city and the photographic.

After spilling out of the basilica and into the overpoweringly bright sun I scurried to a side street to find shade and let my eyes adjust; it struck me that the city of Venice itself has been built with a constant play of light and dark. Narrow alleyways between tall houses provide a maze of disorienting shaded networks, that you emerge from into a sun scorched square, which can overpower the eyes and feel like a shock to the senses.

Fig 11. Streets and canal ways in Venice 2019.

These dark tunnel-like streets leading to chambers of light resonate with ideas put forward in Dr Junko Theresa Mikuraya’s History of Light: The idea of Photography in which she argues that the origins of photography are not the invention of a technical process, but a philosophical discourse with an alternate history which ‘examines the human impulse to reconstruct the photographic or “the evoking of light”’.

Fig 12. Interior Hallway, Venice, 2019.

Mikuraya argues that humans have long thought in photographic terms and can be considered back to Plato’s cave – a dark chamber and a tunnel of light representing ignorance and enlightenment or unknown and known. The camera is a technology born out of long-established human thinking about light and dark and our terrestrial connection to the celestial. The interplay of light and dark in photography now extends to how we view imagery on screens via artificial digital light. Heidegger argues in The Question Concerning Technology that the essence of modern technology is not the technologic but instead is a mode of revealing. Just as the land can be toiled to produce energy such as food, it can be mined by machinery to extract coal which we then burn and the suns energy stored within it powers industrial plants and produces electricity to power our world. A revealing is evidenced by the camera machine recording photons and converting them into electronic signals which convert to pixels containing data, producing images that are revealed on a digital display through digital light. Artificial light sources are appropriate to create a sublime atmosphere within the gallery setting, just as Gagović, Mammadov and Lam used, because of their part of the cycle of the revealing of technology of light and a connection to the sun and our link to sublimity.

Notes for Lumen exhibition:

- Creating darkened spaces with limited light will create a sense of revealing of the works.

- Artificial light such as spotlights or LED strips will be interesting to experiment with to create the right environment. Limited window space in the gallery will mean more control over artificial lights to create the right environment for a sublime experience.

- Technology is a way to connect to light and therefore the sublime, as part of a process of revealing and concealing.

How this research will develop my work.

Being able to carry out on site research enabled me to experience different environments in a city considered to be one of the most inspiring places in the world. This helped me further my understanding of what sublime experiences can be, how to reference them within my own exhibition next year. The research I conducted on this fellowship developed my understanding of how it will be fitting for the exhibition space to use controlled light to create the environment necessary for the potential sublime experience. I learned that for light to have more sublime power there must be a carefully curated relationship with the dark and shadows.

‘And even we as children would feel an inexpressible chill as we peered into the depths of an alcove to which the sunlight had never penetrated. Where lies the key to this mystery? Ultimately it is the magic of shadows. Were the shadows to be banished from its corners, the alcove would in that instant revert to mere void. This was the genius of our ancestors, that by cutting off the light from this empty space they imparted to the world of shadows that formed there a quality of mystery and depth superior to that of any wall painting or ornament. The technique seems simple but was by no means so simply achieved’. (Tanizaki).

I feel I have developed to the stage where I am ready to begin experimenting with materials and processes to create this environment for my own exhibition. This will enable me to close the circle of the idea behind the work: light from the source of the image captured via photography and exhibited with light, creating an experience potentially capable of connecting the viewer to the sublime.

The fellowship spurred on more academic reading which has helped me to make connections, and further my thinking for preparing a PhD proposal, which helped my confidence in approaching scholars and academics to investigate opportunities. I am showing Lumen as part of the Light Sensitive Material Conference organised by Dr Junk Mikuraya in November at the University of West London, which I am attending with the aim of seeking out discussion and relevant advice.

To conclude, I have begun to understand that by exhibiting Lumen in the right context next year I am not completing this research but instead will have finished the first chapter of my fascination with light and photography, and that further developments and discoveries await.

Bibliography:

Burke, E., 2009. A Philosophical Enquiry Into The Origin Of Our Ideas Of The Sublime And Beautiful (oxford World’s Classics). Oxford University Press.

Cubitt, S., 2015. Digital Light. Open Humanities Press Cic

Heidegger, M., 2013. The Question Concerning Technology, And Other Essays (harper Perennial Modern Thought). Harper Perennial Modern Classics.

Junko, M., A History Of Light: The Idea Of Photography. Bloomsbury Academic, An Imprint Of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc,.

Kant, I., 2009. Critique Of Judgement (oxford World’s Classics). Oxford University Press.

Lister, M., 1995. The Photographic Image In Digital Culture. Routledge.

Maria Agnese Chiari Moretto Wiel, The Scuola di San Rocco and it’s Church, Marsilio Guides.

Morley Simon, 2010. Sublime (Documents of Contemporary Art). Edition. Whitechapel Art Gallery.

Tanizaki Jun’ichiro,2006. In Praise of Shadows. Edition. Vintage Books.

Valcanover, F., Jacopo Tintoretto and the Scuola di San Rocco, 2019 ed. Storti Edizioni.

Websites:

- http://lagalleria.vanderkoelen.com/Exhibition/2019/Lore-Bert_SanSamuele_Biennale_Venezia/Illumination-Ways-to-Eureka.html

- https://www.labiennale.org/en/art/2019/national-participations/montenegro

- http://myartguides.com/exhibitions/lore-bert-illumination-ways-to-eureka/

- https://www.facebook.com/285326352390098/videos/434201780693802/

- https://www.chorusvenezia.org/en/church-of-santa-maria-dei-miracoli

- http://www.scuolagrandesanrocco.org/home/

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/San-Marco-Basilica

- https://verityadriana.com/lumen

Documentary:

Francesco’s Venice, BBC, November 2014. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b007zq9t

Super Senses: The Secret Power of Animals. Episode 1: Sight. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b04fhkkl

Art of Faith, 2008. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1327020/

*All images are authors own, recorded in Venice in August 2019.